COSPAR Updates Planetary Protection Policy for Lunar Missions

What Are Category Designations?

COSPAR’s categorization gives guidance on the sensitivity to contamination for a given mission to a solar system target body. The categorization level guides the level of precautions taken during mission development to protect the target body and the integrity of the spacecraft's scientific studies from terrestrial contaminants. Planetary Protection categories for solar system bodies range from Category I through IV, with an extra Category V referring to the protection of Earth itself.

Recently, the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) updated its Planetary Protection policy for the Moon, including adding Category II sub-designations to accommodate missions to different regions. The new Category IIa and IIb designations reflect the importance of the Permanently Shadowed Regions (PSRs) to science and the Artemis generation of human exploration.

Although the Moon retains its Category II status, COSPAR now distinguishes between missions to PSR-containing polar surface destinations as Category IIb, with the remaining 99% of the Moon’s surface being Category IIa. As a result of these new designations, missions to the lunar poles and the rich icy deposits hidden in perpetual shadow need to record their full organic inventory, while most missions to the Moon’s surface still only need to report volatiles released by their propulsion systems.

How Evolving Information Led to Categorization Changes

The rim crest and upper part of the rim of Shackleton crater at the south lunar pole. (Credit NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/Arizona State University)

Earth’s Moon historically has been considered a barren, airless and waterless world. Although scientists detected some water in lunar rock samples brought back by Apollo 14, the Moon was deemed uninteresting and unimportant from a biological perspective. COSPAR subsequently designated the Moon as a Category I body: no Planetary Protection requirements warranted.

Then, the 1990s and early 2000s saw a succession of lunar exploratory missions that determined the water content on the Moon’s surface to be greater than initially thought. Comet and asteroid impacts deposited water ice on the Moon (as it has on all major planets and moons) throughout the solar system’s history. Most of that lunar water is lost back into space as solar radiation decomposes the water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Recent observations by NASA’s SOFIA telescope estimate the Moon is on average 100 times drier than the Sahara Desert. But there are places on the Moon where the deposited water ice is always shielded from the heat and light of the sun.

As the Moon orbits the Earth (which in turn orbits the sun), sunlight bathes the surface of the Moon in monthly cycles. But because the Moon’s tilt on its axis is so slight, deep craters at high latitudes receive sunlight at such a grazing angle that the crater floors never see the light of day. These unlit polar regions remain very cold (as low as -250 degrees Celsius).

LCROSS Impactor Launch (Credit: NASA/Northrop Grumman)

NASA confirmed the possibility of deep and permanent water ice deposits in PSRs in 2009 when NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) sent a 5,000 pound impactor crashing into the south polar crater Cabeus and detected water in the disturbed lunar material ejected into space. The results from LCROSS and surveys from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) prompted COSPAR to reassess the importance of the Moon from a Planetary Protection perspective. In 2008, COSPAR upgraded the Moon to Category II: a body of significant interest relative to chemical and biological evolution of the solar system, but minimal risk of contamination during exploration.

The data collected by LRO is considered essential for planning NASA's future human and robotic missions to the Moon. Large quantities of water at the lunar poles provide an untapped resource for future human explorers regarding water to drink, oxygen to breathe and hydrogen for fuel. From a scientific perspective, the PSRs hold the promise of a pristine multi-billion-year record of the history of icy impacts that could yield essential clues to the early prebiotic chemistry of Earth and its celestial neighbors.

These progressive findings over the last 50 plus years and the importance of PSRs on future science missions and human space exploration prompted COSPAR to call special attention to the contamination concern for PSRs, and subsequently led to the recent addition of sub-categorizations.

Read the press release, “COSPAR updates its Planetary Protection Policy for missions to the Moon’s surface” for more information on the update.

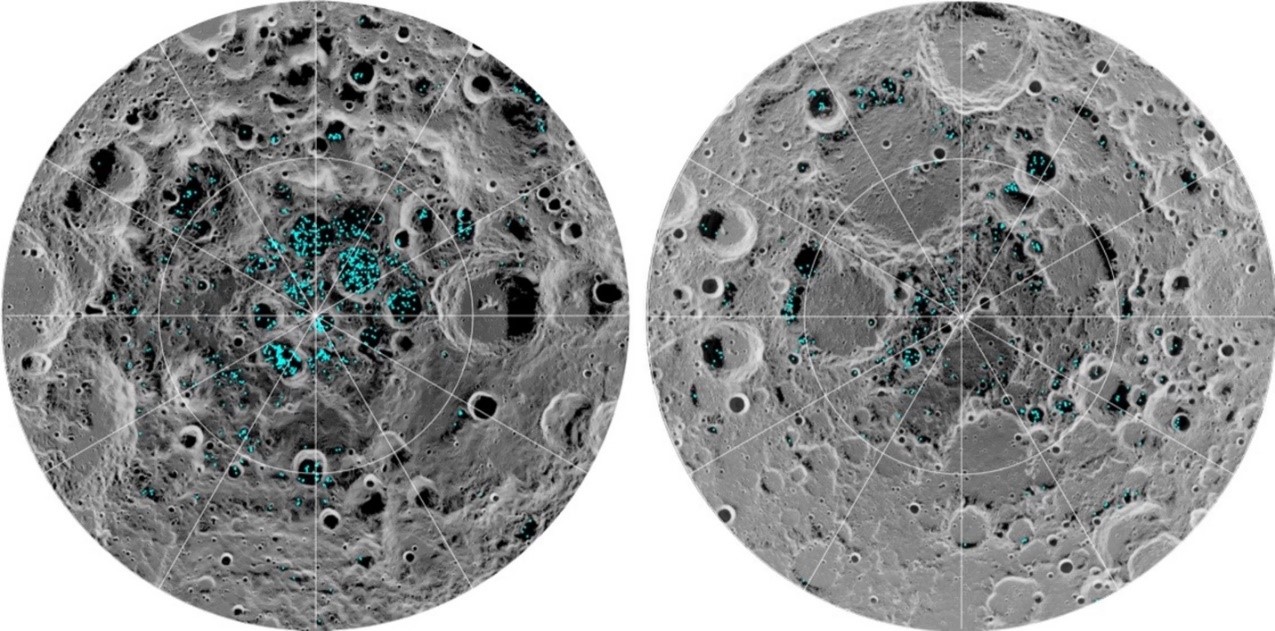

Distribution of surface ice at the Moon's south pole (left) and north pole (right), detected by NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper instrument. Blue represents the location of water ice. (Credit NASA)